Brittany, the summer of 1977 and a group of Scottish cyclists including Vik, Ivan, Dave and yours truly are over there as competitors in the Roscoff–Lorient road race as part of the ‘Festival Interceltique de Lorient.’

A celebration of Celtic music, dance, traditional tests of strength – tug of war and the like – and with a bike race to start things off; just so the foreigners could get a good spanking.

There were participants from Ireland, Wales, Brittany and Scotland.

Off a diet of APR’s (handicapped road races) and time trials it’s needless to say that we enjoyed much of the splendid rolling Breton countryside from the comfort of the ‘sag bus.’

The good thing for us however was that the race was on the first day of the Festival, giving us ten days to pedal around beautiful Brittany and go and watch races.

At one of these races, a criterium on a sunny day at a venue long forgotten, we met an English chap called Julian Wheat who had chucked his job and set up shop in the depths of Bretagne.

I always remember his comment that; ‘I don’t want to get to 40 and wish I’d given it a right go as a cyclist.’

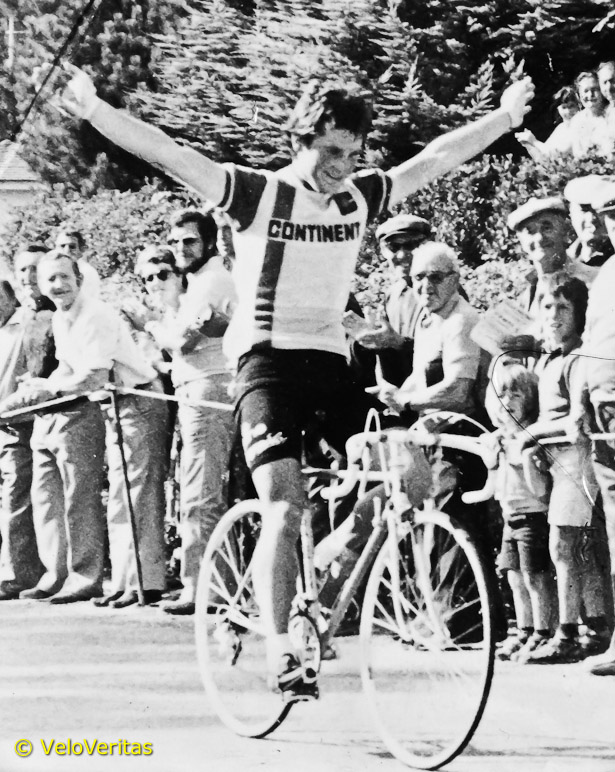

He did give it a right go, making it into the Breton Mafia, avoiding the temptations of “the kit” and winning 15 races during his seven seasons in what is only second to Flanders as ‘Heartland.’

Julian took time out from his career as a successful artist to tell us about those days when there was no internet, Twitter, Skype – and EPO was just a twinkle in a researcher’s eye.

What had you done on the bike in the UK before you headed to Brittany, Julian?

“I’d won the Berks, Oxon and Bucks Divisional Championship four times, twice as a junior and twice as a senior.

“I’d turned 20 and was at a reasonable level for the British race scene.

“I went to France to improve but despite being in what I thought was decent shape I was dropped in my first race!”

You left behind a good job, as I recall?

“I worked with Oxford University Press; it was potentially a very good job as a trainee technical illustrator.

“My coach was Les Woodland (who was also a very well known cycling journalist) who told me that to progress I had to move to Belgium or France.”

Why France?

“I met a guy from the Oxford University Cycling Club who studied French, Trevor Pope – he taught English at a school in Brittany on the university holidays and raced out there, too.

“He said to me, ‘why not come with me?’”

Where did you stay?

“In a farm gîte, (defined as; ‘a simple, usually inexpensive rural vacation retreat especially in France’) near Gourin in Morbihan.

“It was very basic but I was there for two years.

“The first season, 1977 wasn’t so good, as I said I was at a decent level in the UK, when I won the Divisional Champs I rode the last 20 miles on my own but was dropped in my first race in Brittany.

“Many of the circuits were very hard – you’d have to ride up some big hill or other maybe 30 or 40 times. I think it’s different now when British guys come over; they tend to ride the bigger races in France.

“But riding those smaller, tough, local races gave you a great background.”

The first year was tough, you said?

“Yes, it took me four years to actually win a race and it was the second season before I started to find my feet.

“The president of the club I rode for in Bigouden had a construction company with two depots and the guy who ran the one in Fouesnant was mad about cycling; he gave me the use of an apartment above his garage.

“I was there for four seasons; I’d race over there in the summer and come home for the winter and work as a car valeter to get money together for the next season’s campaign.”

Tell us about the ‘Mafia.’

“Ha! So you’ve heard of that?

“The main guy was an Irishman called John Mangan…

***

If you’ve never heard of John Mangan, it’s no surprise because he never turned pro – but here’s what the entry about him in the official history of Ireland’s most famous race, The Ràs – won by Mangan in 1972 – has to say;

“John Mangan: ‘Anyone who knows how it works would realise just how difficult it is for a cyclist, say from Ireland, to break into the French race scene. You have to win respect and to do that you have to win races.’

“Win he did; in fact he won 156 races in all and he ended up as one of the two riders who controlled this group (the Mafia.)

“‘At the end of the day my job would be to tot up the individual placings and then divide the prize money. There would be between 2,000 and 5,000 French francs for the winner and I would ride between four and six races a week.’

“Mangan was the envy of his peers when he brought his Mercedes home in the mid ’70s’s. He was enjoying a high standard of living.

“‘We were probably making as much as money as some top pros. A good amateur could do that and some of the professionals returned to their amateur status. They included Yves Maveleu who was a key figure in the group. There was also Jean Rene Berneaudeau, who would go on to distinguish himself as a professional, winning the Midi-Libre four times.’

“Mangan, himself, would ride against and best some of the world’s best professionals in the criterium races after the Tour de France. He rode alongside Bernard Hinault and became friendly with him.”

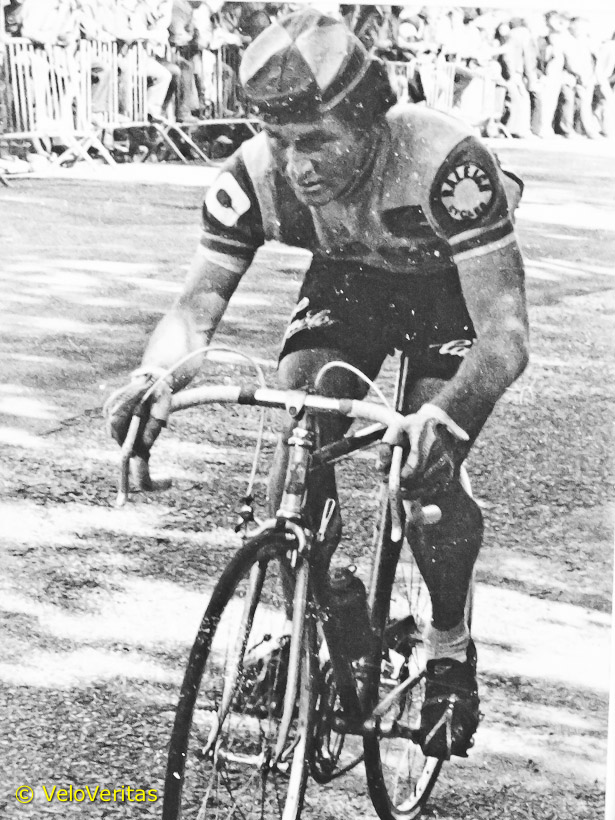

We Scots saw Mangan at a criterium on our trip in 1977; the Ràs history describes him as ‘teak tough’ – which was totally accurate. You could almost see the aura around him.

***

“John was a proper character, he did things his own way. He’s the only guy I ever knew that could put away six bottles of beer in the course of a race.

“I rode a stage race with him early one season; we were in the same team. He rode practically the whole five stages without hardly eating anything because he said he needed to loose weight, having spent the winter in Ireland. I think all the beer got him through each stage!

“But the guy was as strong as an ox – he also had possibly the worst position on a bike I’ve ever seen, he never looked comfortable,and churned huge gears.

“The Mafia was basically a group of the best riders who controlled the races they rode – they didn’t just ride in Brittany, they’d be up in Normandie or down in Bordeaux.

“How it worked was that if you were in a move with them and they could drop you, then they would. But the breakthrough came when they couldn’t drop you; as soon as you were strong enough then they’d let you join the group.

“The other guy who was a member was Dave Wells, the English rider [Wells won the amateur GP des Nations in 1974 and the Circuit Franco Belge in 1975, ed.] who was a very good rider and really nice guy. In fact I remember one race where Mangan, Wells and I were the podium.

“They’d pool all the prize money at the finish and then split it among the group – and remember that it wasn’t just the placings; there was good money for primes, too. I’d get my share but I was also on bonuses for good performances from my club.

“It was possible to make £100/week – when I left to go to Brittany I was on £20/week with my job.

“No wonder Wells and Mangan drove Mercedes.”

How did your palmares end up?

“I won around 15 races all-told but only five of those were on my own merit – the rest were with the Mafia.

“I was always top ten but I’d have to take my turn at grabbing primes or chasing down breaks.

“But I didn’t mind that, I loved it.”

Was there ever any thought you might turn pro?

“There were two years where I was stomping, winning against ex-pros but not riding the Classics.

“A guy from CSM Puteaux – which was one of the big Paris clubs and a feeder team for the pros – noticed me and I was invited up to Paris.

“They offered me a ride for the next season but it meant I would have to have spent the winter in Paris, which I didn’t want to do because I had no work there – so I went home to Oxford.”

How big a factor was the kit (doping), back then?

“In the amateur ranks riders knew that there was no point in taking it if they wanted to turn pro.

“The best riders rode clean as amateurs and only took it when they had to as pros.

“I only ever dabbled once, one of the Mafia guys said to me; ‘here, take this!’ He gave me a caffeine injection before the final stage of a race – it was the most painful injection I’ve ever had in my life!”

You quit racing at just 28?

“I’d had my time and didn’t want to suffer any more – I used to have train so much and so hard to be successful.

“But I was still feeling wander lust and spent the following 11 years travelling.

“Having always cycled, it seemed natural that the best way to travel was on the bike.

“I’d work 5-6 months of the year, so as to finance travels to such far flung places as the Rocky Mountains of America, and Alaska”.

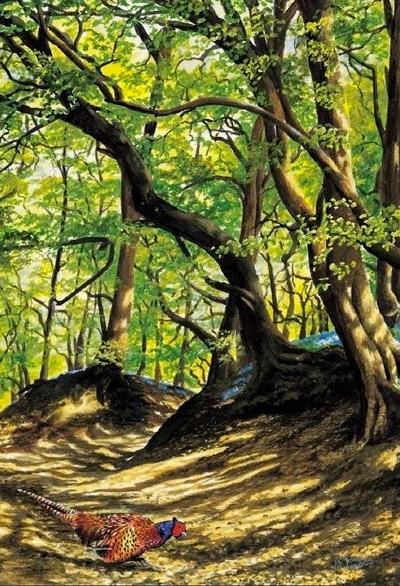

And you live in France, now?

“In the Correze area, I bought a property down here and now I paint full time for a living.

“I still ride the bike when I can but the weather has been so bad.

“There used to a big bike racing culture down here; I believe Arthur Metcalfe and Bill Bradley based themselves in the area, back in the day.

“But up in Brittany it’s still very much part of the culture, every village has a fête and there’s still a lot of racing.”

Regrets?

“Age makes you philosophical; I’d gone as far as I could, I was as good as I was ever going to get.

“I didn’t have the physical capabilities to be a really top rider – you need the huge lungs and the big slow heart.

“But I enjoyed my time in Brittany, and I love my life here …”

And if you’d like to see some of Julian’s work, check out his website julianwheat.com.