In Part One of Phil Cheetham’s Memories we heard about how, in 1967, he made his way to Troyes in France’s Champagne region to spend the summer months racing with one of the best teams in the country, UVA Troyes, sharing a house with future pro Derek Harrison, and ‘accidentally’ winning a race.

In 1972 he rode the legendary Peace Race, with never a dull moment. Here’s Part Two of Phil’s story…

* * *

By Phil Cheetham

Behind the Iron Curtain for the Peace Race, 1972

On the 17th of February the BCF inform me that I’ve been selected for the Peace Race, the 25th edition.

I really want to give it a go this year.

Early in February I run out of money. I’d only worked seven days on the Post Office since the end of the last season.

I ask my previous sponsor, André Vistel, who runs a helicopter crop spraying business if he can take me on for a while. His firm is called Phitagri and his slogan is “du veau à l’hélicoptère” (from calves to helicopters). I was never really sure what that meant.

He says he can.

I’ll be helping the mechanics in his warm, well-lit workshop where about half a dozen helicopters are being overhauled.

But I will have to clean the toilets each day.

That’s the type of man he is; he didn’t want to see me being treated like a privileged worker in front of all his other employees. He’s one of those bosses who will give his workers a hand unloading a lorry if he passes that way.

I work there part-time for nine weeks until the 2nd of April. I take every Thursday off to get in a long training ride in the morning.

In the afternoon I go out with the “Ecole de Cyclisme” (the cycling school) sponsored by Phitagi.

It’s run by Patrick Odin, the son of William Odin who was the mechanic for the French national squad in the Tour de France during the time our Sports Director, Marcel Bidot, was the selector and manager.

Over one hundred schoolboys turn up every Thursday where they take part in bike handling exercises, sprints and short races.

On the other days I ride to and from work, generally taking a long route to get home, so I’m riding about 75 km per day.

I have a bad crash in the club’s second training race on the 12th of March.

These are ‘real sponsored handicap races’ with prize money even though the amounts are fairly small.

I fly over the handlebars in the sprint for the line and fall heavily on my back which soon turns all colours of black and blue.

My bruised back hampers me for a while but doesn’t affect my training programme.

The English journalist, John Wilcockson drops in to see me one day in the workshop and writes a two page article about my build-up for the Peace Race and the Phitagri cycling school in the ‘International Cycling Sport’ magazine.

By then I have already done 3000 kms in training.

Due to the new French Federation regulations we don’t ride our first race until the 19th of March.

Two weeks later it’s already the club’s classic, Paris-Troyes. Alan Mellor and Bryan Edwards arrive two days before the race.

I puncture whilst in the leading echelon and abandon after 60 km; following team cars aren’t allowed. Jacques Esclassan wins the race.

Then Alan and I really begin to step up our training and get in loads of kilometres whatever the weather.

The Tuesday after Paris-Troyes Alan and I go to Paris to get our Polish and Czechoslovakian visas. In the Polish embassy they tell us it will take at least a week and that we will have to come back again.

That was until they see on our application forms that we will be participating in the Peace Race, and 10 minutes later we have our visas.

We have two races the next weekend.

I finish fourth in Azay-le-Ferron and second in Chateaurenard where I go to the doping control.

The next weekend is the Tour de l’Aube. There’s a good field with 101 starters including three riders preselected on the French squad for the World Team Time Trial championships.

I finish second on the first stage and fourth on the second. I’m lying fourth overall before the 14 km individual Time Trial on Sunday afternoon.

My DS, Marcel Bidot comes to see me; “I’ll follow you,” he says, “but I want to see you win the Time Trial and the overall classification“.

It had never crossed my mind. I was thinking I’d do well to hang onto my fourth place.

Marcel Bidot has already followed Jacques Anquetil, Raymond Poulidor and Roger Rivière in Tour de France Time Trials.

He continuously shouts at me out of the team car window. I can’t let him down and gave it all I have.

I come home with the best time beating the three French Olympic squad riders; Jean-Claude Meunier by 21 seconds, Alain Meunier by 25 seconds, and Claude Duterme by 31 seconds, as well as the overall leader Roland Eloi by exactly one minute.

Enough to take the overall classification by 19 seconds – thanks to Marcel.

I now know the difference between riding as hard as you think you can and riding at the extreme limit of your physical capabilities.

The next weekend we ride an international three day event in Sedan near the Belgian border; three separate races with an overall classification on a points system.

My teammate Claude Chabanel wins the first stage, the ‘Prix de Slavia‘, on Friday.

I win the sprint for second on the track in Sedan.

On Saturday I win the second stage, the ‘Prix Erika‘, 54 seconds ahead of Alan Mellor in the cold, wind and rain.

I take over the race leader’s jersey.

We control the third stage, the ‘Prix de l’UCI‘, won by Alain Bauchet from the Pédale Châlonaise.

I win the bunch sprint for fourth and hold on to the white jersey.

Alan finishes third overall.

A British team is riding, amongst them a certain Pat McQuaid who finishes 10th overall.

He had a good amateur career (he won the Tour of Ireland twice) before turning pro for Viking cycles. In 2005 he was elected president of the UCI in the troubled times of mass EPO doping.

We ride another race on Monday but without much success (I finish 10th).

Two days later, Alan and I leave to ride the Berlin-Prague-Warsaw Peace Race.

* * *

My form can’t be better.

We fly first to Prague then board an old, decrepit ‘plane, with smoking engines and bald tyres, for the short flight to Berlin.

We are housed in a large, high-class multi-storey hotel. Several floors are reserved for the riders and staff.

A large group of police motorcyclists are posted on the forecourt to escort and keep an eye on us whenever we leave the hotel for a ride.

Late in the afternoon, I go out to test my bike; two outriders clear the way and wave the traffic aside.

I immediately turn right and lose them.

I ride unhindered through the tram-lined streets and wide avenues of East Berlin. The featureless buildings look grey and dreary.

Suddenly I’m opposite the Brandenburg gate.

A green lawn lies before me guarded by barbed wire, trip wires, armed patrols and watchtowers.

West Berlin on the other side appears attractive, fresh and inviting with the 368-metre high Fernsehturm, a TV tower built just three years before, towering proud in the distance.

The sky is darkening, it’s getting late. I turn round and ride back to the hotel.

Nobody bothers me.

The next day we do a 50 km ride, this time well-escorted by the outriders and our team car.

That evening there’s a huge reception at a venue about four kilometres from the hotel. Tom Pinnington, our “amateur” team manager and the rest of the squad decide they will do some sightseeing and walk back to the hotel.

I can’t believe it, you don’t walk any distance, let alone four K, on the eve of an important event. I hitch a ride with the French team.

The British and French teams often have a mutual agreement, if one of the team cars moves up to cover the break the other car will cover the two teams in the peloton.

I know their manager Robert Oubron and their mechanic André quite well. Andre’s only shortcoming is that he doesn’t like oiling the chains as it makes the bikes more difficult to clean but the British mechanic, if asked nicely, will usually oblige.

Back at the hotel, it’s quite obvious that our bags have been searched. Whoever it was, they made no effort to conceal the fact.

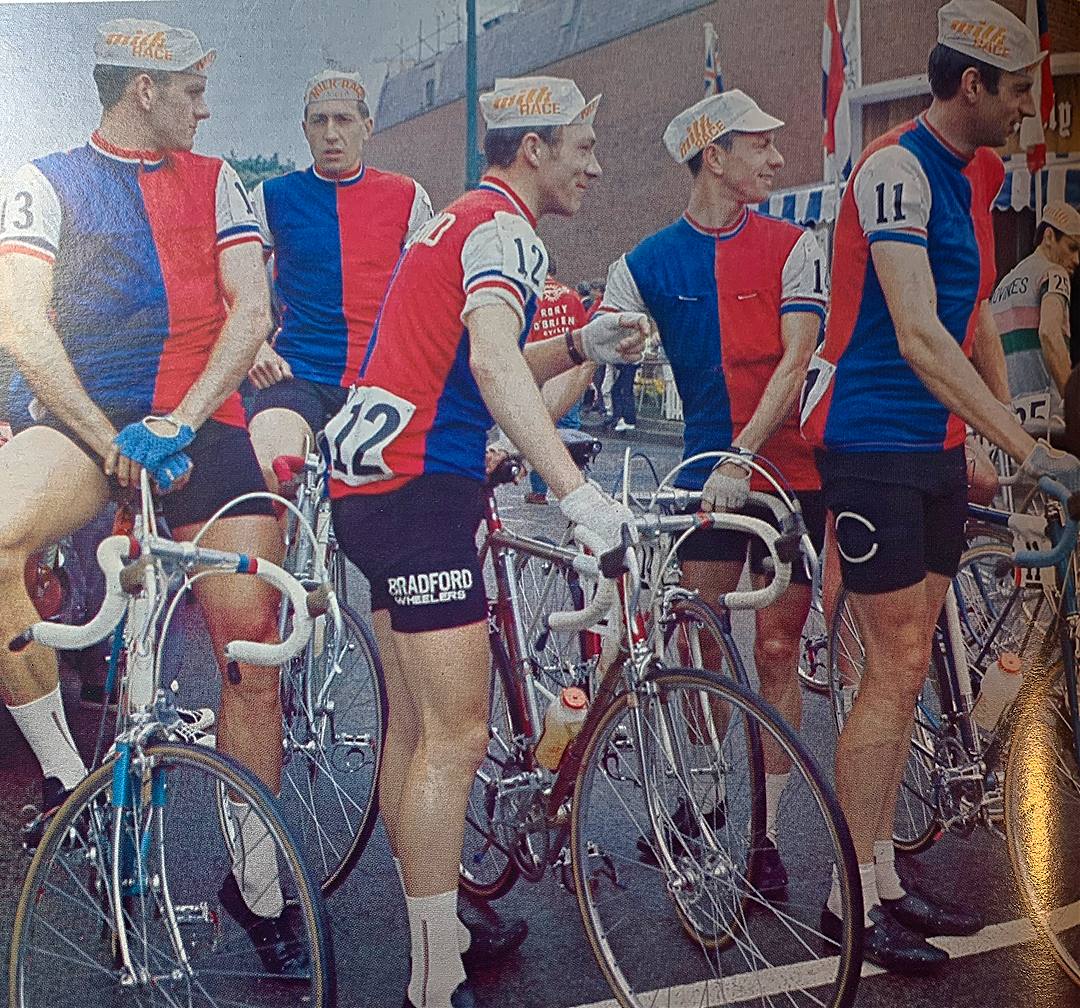

The teams competing are from the Soviet Union, Germany, Czechoslovakia, France, Italy, Poland, Morocco, Cuba, Yugoslavia, Belgium, Finland, Denmark, Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania, Norway and Great Britain.

That makes 17 teams in all and 102 starters.

The Peace Race is dubbed the Eastern Bloc Tour de France. The crowds are enormous, up to 60,000 at the finishes, mostly on cinder tracks which are very tricky to negotiate, especially as I’ve never ridden on one before.

Flags and pennants are flying everywhere you look. Even when we take the bus to drive to the start, the roads are lined with clapping flag-waving crowds. We wave back as we go past, like the Queen in her stately carriage.

Each morning we leave our bags in our rooms and find them already waiting for us when we move into our rooms after the stage; each time they have been tampered with.

At the finishes, like each rider, I have a designated boy wearing my number.

He seeks me out, gives me a drink and something to eat, puts a blanket over my shoulders, looks after my bike and takes me to a long line of waiting buses which set off almost immediately for the hotel, even if only a few riders are on board.

Stage One

The first stage is a nine kilometre out-and-back Time Trial in Berlin.

120,000 people line the course.

I’ve picked up a bout of bronchitis and my breathing isn’t too good.

I finish 29th, 22 seconds down on the joint winners Takacz from Hungary and Neljubin from the USSR.

Ian Greenhaigh finishes 70th, Alan Mellor (suffering from hay fever) 72nd, Sandy Gilchrist 82nd, Mike Potts 88th and Howard Darby 93rd.

Maybe I was right not to walk back to the hotel the previous night.

Stage Two

The text in italics below is from Cycling Weekly and written by Richard Froude.

“The following day’s second stage circuit race around Berlin was significant for the violent switching throughout the 121 kilometres and two of the main hopes, Janusek of Poland and Labus of Czechoslovakia, came down in the melee and broke their collarbones.

“The East German Michael Milde comes home first.”

We are all placed equal 26th in the bunch.

Stage Three

“Violent switching and crashes were again the order of the day on Stage Three and that’s where Régis Ovion (the reigning world amateur champion and Tour de l’Avenir winner) said goodbye in a major crash three kilometres from the finish in Magdeburg.

“It was obviously not the best of days for the French for Guy Sibille came down in the same crash and broke his collarbone.“

It happened just three or four places ahead of me, Régis Ovion was switched into a roadside post.

“Britain’s fortunes were mixed, with Cheetham and Mellor finishing in the leading bunch.

“Mike Potts lost contact at Burg, after 139 of the 163 kilometres and finished alone at 4-55.

“But it was Sandy Gilchrist and Ian Greenhaigh who provided the highlight of the day. The train of events started at Burg when Gilchrist was brought down and wrecked his handlebars.

“Greenhaigh was on his wheel at the time and also came down. Gilchrist got a spare bike and the pair started to chase, but they were further delayed when Greenhaigh collected a puncture at the time when the team car was ahead with the bunch.

“After affecting repairs they linked with a chasing East German, who for some reason was unwilling to work. Eventually he was forced to the front, but only to switch Gilchrist into Greenhaigh, with the result that the Scot’s rear wheel was smashed.

“He borrowed a bike, complete with tourist handlebars, from a young bystander then he and Ian rode the final eight kilometres to the stadium finish. As they emerged from the tunnel a tremendous roar erupted from the 45,000 spectators.“

[Friend of VeloVeritas, Ivan, supplemented this part of the tale for us:

Sandy and Ian came down about 8 km from the stadium in Magdeburg. Sandy’s bike was badly damaged and the team car was nowhere in sight.

At that moment a 14-year-old East German boy named Holgar Trenck handed Sandy his heavy touring bike and pointed in the direction of the finish only 8 km distant. Ian and Sandy made their way to the finish, Ian pushing Sandy for much of the way.

The crowd in the stadium had been informed of the unfolding drama by the stadium speaker and both riders received a splendid ovation from the 45,000-strong crowd in the Ernst Gruebe Stadium.

Meanwhile, Holger Trenck had been picked up by a race organisation car and was at the finish to get his bike back from Sandy. As a reward he was invited to the GB team table for the evening meal.

This story made the national press in the ex-DDR. This type of story, with Peace Race riders being helped by spectators has a long tradition, being part and parcel of the propaganda of the race (ie. riders and spectators united in their common desire for peace and solidarity between nations).

There have been many of such incidents in the Peace Race, another example is the English rider John Woodburn, who also borrowed a spectator’s bike to finish a stage.]

“But behind these two was another Briton Howard Darby who had been delayed by a crash and was the last rider to finish, almost 34 minutes down.“

Milde again wins the stage, I finish 30th and Alan 39th. Overall Milde retains the leader’s jersey of course.

I’m 20th at 2-1, Potts is 77th at 7-34 and the others are well down.

Stage Four

Stage Four from Ascherleben to Erfurt is 170 km long.

“Michael Milde, East Germany’s wonder 23-year-old, scored his third consecutive victory when he outsprinted a group of 40 riders at Erfurt Stadium, with no British rider strong enough to find his way into the group when the crunch came with 20 kilometres remaining.

“‘I knew I should have been in one of the two leading echelons as soon as I felt the wind, but there was no room for me and I was just blown off the back‘ said Phil Cheetham.

“For Britain it was a sad tale, with second best man Howard Darby losing 5-9, while poor Potts, who punctured, was left waiting for his team car, 16th in the convoy, and lost at least two minutes before restarting in company with Ian Greenhaigh, who was already trailing and suffering from his injuries of the previous day.“

Sandy Gilchrist and Alan Mellor were even further back and they nursed injuries and hay fever, which plagued Mellor throughout.

I finish 48th at 1-40 and drop from 20th to 40th overall.

I knew the race was going to be difficult.

There are no professional ranks in the Eastern bloc countries to cream off their best amateurs, so we are riding against the very best of their state-sponsored riders and we’re completely unaware of the state-organised doping programmes, these being extremely sophisticated, especially in East Germany, as we now know.

Stage Five

Stage Five is 151 km from Erfurt to Gera.

I finish 87th at 35-31 and drop again in the overall standings to 82nd.

“A glimmer of hope filtered through on this stage, with Darby getting home in the main bunch only a minute behind East Germany’s Karl-Heinz Oberfranz, who took the stage, from nine others, but Gilchrist and Mellor were eliminated.

“‘I was feeling good for the first time today,’ said Cheetham ‘so I went for a long one at the first prime to test myself and found that my bronchitis had disappeared’.

“But his joy was short-lived, because after 26 km he crashed as he tried to avoid two Poles and to make matters worse Potts hit him in the back.

“Servicing Cheetham was slow, because a broken wheel developed into a stripped spindle and a spare bike had to be given, and by this time the bunch was miles up the road.

“The stage is again won by an East German, Uberfranz.“

Throughout the day I’m with a small group trying to get discreetly to the finish.

But every time we ride through a town or village the local band waiting patiently in the bandstand strikes up again and plays rousing music as we ride through the cobbled streets dodging the tramlines.

Each day during our evening meals a small orchestra concealed behind potted plants plays chamber music while we eat. They are dull and staidly dressed.

On the third evening we decide we will give them a little clap at the end of one of their pieces, the Poles sitting next to us join in.

Pale faces peer out from behind the green vegetation and soon more teams are joining in the clapping. The players begin to smile broadly, their music becomes less sedate and improves greatly.

The Russians are not amused.

There is always an enormous bowl of fruit on each table. We can see that there is none in the local shops. We soon get into the habit of leaving the table with a much fruit as we can carry and hand it out on the forecourt of the hotel to whoever’s there; there are always people waiting hoping to get an autograph or a souvenir of some sort.

The next day is a rest day in Gera.

We are taken to see a modern model factory. The photos of the best weekly and monthly workers are displayed proudly on the walls. We are given presents.

We also visit a dull model apartment where a teacher and his family are housed.

We have no time to go for a ride.

Stage Six

Stage Six is 159 kilometres from Gera to Karlovy Vary. We are heading for the mountains.

I go to see André, the French mechanic, to find out which gears we need, Tom Pinnington has no idea.

It turns out to be very cold, we are unaware of the weather forecast and have no appropriate clothing.

I’m going quite well until, with no warning, I’m down and sliding along a cobbled street.

I get back on, catch the bunch and on a long straight hill then bridge the small gap up to the break.

Suddenly I begin to shiver probably from the shock of the fall and the severe cold which has now set in.

“A black, black day for Britain, when of the six who started only one, Ian Greenhaigh, reached the finish – a quagmire at Karlovy Vary that only a few hours earlier had been a cinder track.

“Ironically, Mellor and Gilchrist had been reinstated on appeal and at the start, although the rain was falling steadily, there was no indication of the drama that was to unfold in the next four hours.

“In fact, it wasn’t until the stragglers arrived, some in pathetic condition, that anyone realised just how bad it had been.

“The severe cold, the cobbles and the rain killed many a will, and when Darby clawed his way into the frontier post on the Czechoslovakian border he found he was well down the queue.“

I make it to the top of the climb but my whole body is trembling and my teeth are chattering. I begin the descent but can’t feel a thing. I’m numb all over.

I see another rider running down the hill to try to warm up so I do the same. It makes no difference. I sit down huddled against a pine tree.

The next thing I know, a medic is helping me walk to an ambulance, my bike is being put in the broom wagon. I want to stop them but can’t react.

They leave me at the frontier post, I’m not alone. There’s a huge wood stove burning. We are all shivering.

Some of the guards go out to scrounge some dry clothes from the inhabitants of the border town.

We look a strange, odd lot dressed like Hungarian refugees our soggy racing kit strewed on the floor.

“Potts, Gilchrist, Darby and Mellor all sought the sag wagon, already full to overflowing while others, like the Belgian Isidore Weemans, arrived at the finish quite literally blue”.

My teeth are still chattering when we get to the hotel in the beautiful spa town of Karlovy Vary.

It takes me hours to get some warmth back into my body.

The record shows that 27 riders abandon that day.

So that’s it for the Peace Race. I’m bitterly disappointed; we just weren’t prepared for the conditions that day.

We are staying in a magnificent, imperial-style hotel with massive rooms and elegant balconies; the toilet is up on a pedestal, alone in a large room.

I have a kilo of sugar lumps in my bag that I’ve brought over from France; we were told that it is a rare commodity.

I give it to the maid when she comes to clean the room.

She gets down on her knees to express her gratitude, saying “thank you, thank you,” over and over again.

So that is more or less the end of the adventure.

The next day we travel to Prague by bus. We stay there overnight before flying back to Paris.

Clearing immigration in Czechoslovakia is intimidating. The official looks at every single page in my passport for at least five seconds then looks me straight in the eyes for another five seconds without blinking once.

The Russian Neljubin takes over the race lead from Milde but in the end loses it to the Czech Vlastimil Moravec.

GB sole survivor, Ian Greenhaigh finishes the race in 55th position.

* * *

‘UCI Weather Protocols?’ Not in the Peace Race… With thanks to Phil for another great tale.